How does the layout of a space shape the outcome of the activity in it?

Can we make the connection that the recent paralysis of British Parliament is the result of the dysfunctional layout of the House of Commons?

I believe people have a misguided nostalgia that the form of the current parliament building is essential for the UK’s democratic and functioning government.

No matter how you define democracy, the people we vote for should have a conducive space to do this work in and not be in a permanent state of conflict. In an increasingly polarised world and less definite majorities they need spaces in which to collaborate, and find solutions for the common good.

The Precedent of the British Parliament

The precedent of the current House of Commons is based on the former chapel of St Stephen’s (illustrated) with its rectangular shape and bench seats. From contemporary illustrations it looks like the space functions ‘in the round’. The horseshoe seating arrangement allows for a symbolic and physical collaborative connection. You can imagine the healthy debates but you can also see how a consensus could arise. This was the building of government from 1547 to 1834, almost 300 years. Is this the actual model of the prized British Democracy?

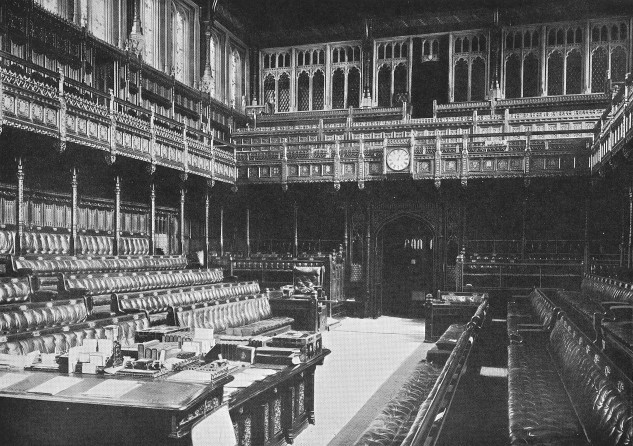

The House of Commons 1852 – 1941

The move to current Westminster Palace in 1852 was to a space based on the St Stephen’s Chapel but with a subtle change of dimension and emphasis. (Illustrated) No longer was there the unifying horseshoe layout, but two stark opposing sides.

In this space the two party system became dominant, which has persisted until now.

The Rebuilt House of Commons 1950 – Present

After the destruction of the House of Commons in WW2 Churchill was very keen that the entire edifice should be rebuilt as before “in all essentials”. This was completed in 1950 (see illustration).

“We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

Winston Churchill

He is clearly right in this statement; it has proved impossible to have any functional coalition government of consensus in this space. Perhaps it was Charles Barry & Augustus Pugin who did not incorporate all the ‘essentials’ in the rebuilding in 1852, and perhaps we should consider this confrontational space may not be authentic ‘model’ for British Democracy.

Miles Taylor, Professor of History at York University makes the case that the rebuilding of the House of Commons from 1943-1950 was a deliberate act to support the two party system. (click for link to his article)

Interim Parliament 1941 – 1950, a Better Result, a Better Model ?

When Parliament moved out of its current space after it was destroyed by bombing in 1941, wartime necessity required a system of collaboration. The business of the Commons was mostly conducted in the space of the House of Lords which was not significantly damaged. (Illustrated) Whilst having similar dimensions the essential character of the space was quite different. This space is less deliberately confrontational. This space allowed for successful wartime coalition up to 1945.

The same space also facilitated the launch of modern Britain between 1945 – 1950. It was here that the introduction of the National Health Service was launched; reforms bringing progress, social inclusion, well-being and encouragement of the arts were conceived in this temporary accommodation.

Now – Opportunity to Improve

We now have a unique opportunity to revisit this discussion – proposals have been announced to carry out an essential renovation programme at the Palace of Westminster. A provisional agreement has been made to temporarily re-house Parliament for a huge amount of money, recreating the current dysfunctional layout. (Illustrated)

The temporary green bench accommodation is proposed as an almost exact replica of the existing. However, the furniture layout of the House of Commons is not sacrosanct.

The symbolism of recreating the red line (the spacing is allegedly greater than two sword lengths apart to prevent opponents spearing each other), defines that the paralysing conflict will remain.

Why not create a different temporary space better suited for dealing with the impending climate crisis, which will require cross party collaboration (just like wartime crisis did)? Why keep the dimensions the same? Why not re-introduce the essence of St Stephen’s Chapel with its horseshoe collaborative layout which was lost in translation when Parliament moved to the Palace of Westminster?

Facing new political crises these aspects should all be reconsidered urgently. To do so would be in the interests of the country’s well-being and democratic process.